- Why Mining Matters

- Jobs

- Safety

- Environment & Operations

- FAQ

- Links

- Fun Stuff

Mining makes temporary use of land and then land is reclaimed to prepare it for its next use.

Nova Scotia companies must get government approval of reclamation plans and post reclamation bonds (money in escrow, basically) for reclamation before getting operating permits. This ensures mines and quarries are properly reclaimed after extraction is done.

Here are some examples of how former mines and quarries are often hidden in plain view!

Amherst, Red Stone Quarry Belmont Pit Blockhouse Cape Breton Highlands National Park Cheticamp CoalburnCottam Settlement Dartmouth Crossing Dartmouth, Leighton Dillman Park Dartmouth, Shubie ParkDingwall East River Point Gold River Halifax, King QuarryHalifax, Merv Sullivan Park Halifax, Point Pleasant Park Halifax, Terence Bay Wilderness Area Inverness Irish CoveKejimkujikKempt ShoreLunenburg County, The Ovens Park Malagash Marble Mountain Mica Hill Milford Moose River Newport Station Nictaux Granite Quarry Point Aconi Shelburne, Islands Provincial Park Spryfield St. Margaret’s Bay St. Rose Stellarton Stellarton, Allan MineStellarton, Dorrington Softball Complex Stellarton, Foord Pitt Sullivan Creek Thorburn Truro, Kiwanis Park Walton Gypsum Quarry Walton Barite Mine Westville, Acadia Park

Amherst, Red Stone Quarry

Today, the Amherst Red Stone Quarry is a lovely pond in a field.

It operated from about 1889-1914, providing sandstone for many heritage buildings including Amherst’s Bank of Nova Scotia (built 1907), Trinity-St. Stephen’s (1906) and the First Baptist Church (1895). The quarry was on James Donalds' farm, east of Willow St.

Belmont Pit

The Belmont sand and gravel pit, before and after!

The Belmont Pit, in Colchester County, was opened in the late 1900s to provide aggregate for construction. It was reclaimed in 2016 and today, it is a reclaimed and thriving wetland.

The boundary of the former pit is outlined in red. Notice how the reclaimed area looks the same as the areas outside the pit’s boundary. Blending a former mine, quarry or pit back into the natural environment is the goal of most reclamation projects. In time, people likely won’t realize that an industrial operation was ever there.

Blockhouse

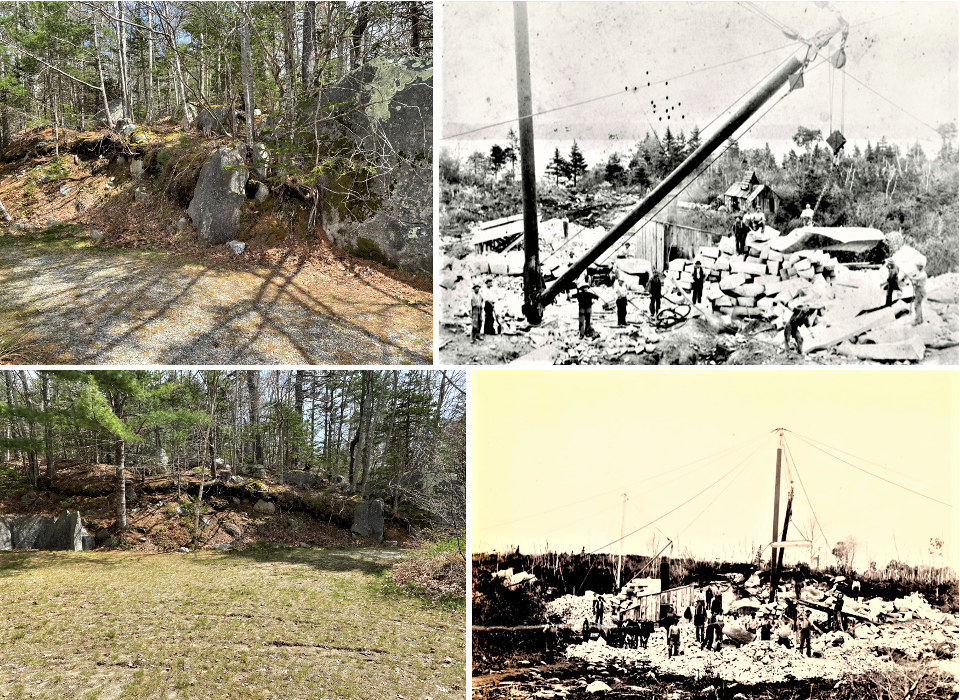

In 1885 a gold-bearing boulder was discovered in Blockhouse, Lunenburg County, but it wasn’t until 1896 that a significant gold deposit was found. The Blockhouse Mining Company sank two shafts but the mine closed down not long after.

In 1898 a new owner, T. Foster, took over. The mine had produced 3259 ounces of gold (worth about $5 million at today's prices) by 1902 when it shut down again. It was mined again briefly from 1935-38.

Today the Blockhouse gold mine is a forest.

To learn more about Blockhouse please go here.

Cape Breton Highlands National Park

Some of Nova Scotia’s most beautiful parks and protected areas contain former mines and quarries – including the Cape Breton Highlands National Park, where mica was mined on Mica Hill in the 1880s.

Cheticamp

The Cheticamp gypsum quarry in Cape Breton operated from about 1907 to 1939. The company later donated the land to the community and today it's a beautiful swimming hole and hiking trail. Nova Scotia has long been one of the world's largest suppliers of this key ingredient in wallboard/drywall.

Coalburn

The Coalburn coal mine was reclaimed in 2005 and today it is beautiful rolling fields with a pond and lots of wildlife.

Cottam Settlement

In 1999, a bulk coal sample was extracted in Cottam Settlement, about seven kilometres from Debert. The mine didn't continue but reclamation did.

Colchester County also had several historical coal mines in the 1800s and early 1900s in Debert, Kemptown and Belmont.

To learn more about the Cottam Settlement please go here.

Dartmouth Crossing

Reclamation usually means returning a mine/quarry to nature but it can also mean preparing it for development. This is Dartmouth Crossing in 2004 when it was the site of two quarries and in 2017 after it had become one of Nova Scotia's premier shopping districts.

Dartmouth, Leighton Dillman Park

Some of Nova Scotia’s most beautiful parks and protected areas contain former mines/quarries!

Dartmouth’s Leighton Dillman Park had a mine in it in the 1840s, the Cleverdon Copper Mine, near the park’s entrance on Windmill Road. In addition to copper, the mine also produced some iron and gold.

Dartmouth, Shubie Park

Shubie Park in Dartmouth contains a former quarry that is now a baseball field and campground. The quarry’s rock crusher used to be where the bike track is now!

Dingwall

The Dingwall gypsum quarry in Cape Breton operated from the mid-1930s until 1955. The company reclaimed it and now it's a beautiful site that combines white gypsum outcrops with forest and ocean views.

East River Point

Former mines and quarries are often hidden in plain view!

This is a limestone quarry in Lunenburg County that operated for a century, helping build some of Halifax’s oldest buildings. Today it is a lovely lake.

The Lordly quarry’s limestone had what a 1914 report called “hydraulic properties,” meaning its limestone was good for producing hydraulic cement, which solidifies quickly. Non-hydraulic cement can take days to harden.

According to the Geological Survey of Canada, limestone from the quarry was used in the cement in the “old barracks and many of the oldest buildings in Halifax.” The “old barracks” were the Wellington Barracks, built in the 1850s of bricks held together by cement/mortar. The barracks still stand at Canadian Forces Base, Halifax-Stadacona.

The Mersey Paper Company operated the Lordly quarry from 1930-49, using the limestone in its Liverpool pulp and paper mill.

To learn more about the East River Point quarry, please go here.

Gold River

Lots of places in Nova Scotia were named for their connections to mining – but Gold River is NOT one of them!

Gold was discovered in Gold River, Lunenburg County, in September 1861 by Daniel Dimmock of nearby Chester. However, Gold River is believed to have been named after a Mr. Gould, an early settler, and it’s original name was Gould River. The name was changed to Gold River before gold was discovered there.

The area produced 7610 ounces of gold between 1881-1940 and today it is beautiful natural space and a bunch of homes on Lacey Mines Road.

To learn more about Gold River please go here.

Halifax, King Quarry

King Quarry in Purcell's Cove is likely the oldest quarry in Halifax. It began in the 1700s and its ironstone and slate were used for many historic buildings like the Citadel and Martello Tower. Like many former mines/quarries, the site is now a beautiful natural spot.

Halifax, Merv Sullivan Park

Merv Sullivan Park in north-end Halifax is often called The Pit by people who may not realize that it was actually a gravel pit! Today it’s a lovely urban park and baseball field.

Halifax, Point Pleasant Park

The Quarry Pond in Point Pleasant Park was a quarry in the late 1700s and 1800s, one of a number in the park that helped build its forts, roads and walls. It later filled with water and became the pond we know today.

Small holes were made in the slate with hand-held drills. The holes were filled with explosive to extract the rock. The stone was then shaped by hand for the buildings in which it was going to be used. Some drill holes can still be found at the pond.

Halifax, Terence Bay Wilderness Area

Former mines and quarries often become parks and protected areas. For example, the Terence Bay Wilderness Area includes two sites that were quarried from 1900-1907 for building stone used in some of Halifax’s most beautiful buildings, such as the Bank of Commerce Building (aka Merrill Lynch Building, 5171 George Street) which was built in 1906.

Inverness

World-class Inverness golf course Cabot is on the site of a former coal mine. Coal was first discovered there in 1863 and was mined until 1958. Today, the reclaimed site is contributing to the community in a different way – with an amazing golf course that is creating jobs and attracting tourists to this beautiful corner of Cape Breton.

To learn more about Inverness / Cabot Links please go here.

Irish Cove

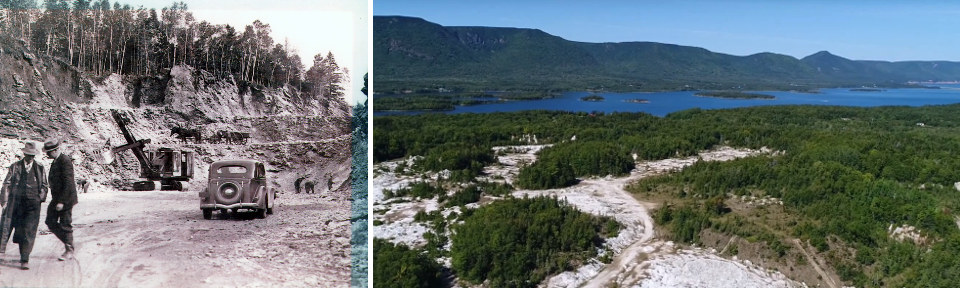

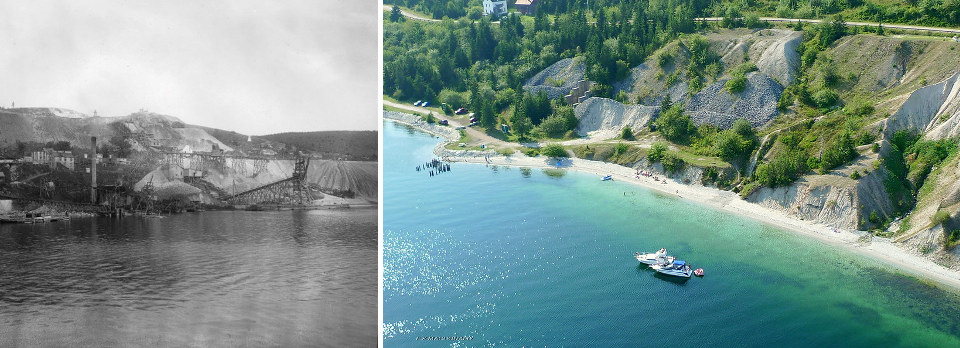

The Irish Cove limestone quarry, before and after!

This reclaimed Cape Breton quarry, on the eastern shore of the Bras d’Or Lake, started providing metallurgical limestone in the 1960s that was used as flux in SYSCO’s steel mill in Sydney. (Flux is used in the smelting process to promote fluidity and remove impurities in the form of slag.)

The site was reclaimed in 2003-04. Soil and over 100,000 tons of leftover crushed limestone were used to contour the quarry’s slopes for safety and to re-vegetate it. Today it’s a beautiful greenspace.

Kejimkujik

Some of Nova Scotia’s most beautiful parks and protected areas contain former mines and quarries – including Keji! Gold was discovered in 1888 in West Caledonia, in an area that is now part of Kejimkujik National Park.

To learn more about the Kejimkujik mines, please go here.

Kempt Shore

Gypsum quarrying began in Hants County in the 1700s. There have been many quarries in the area over the years, including two in Kempt Shore. The Kempt Quarry Recreation Site is now a beautiful lake.

Lunenburg County, The Ovens Park

Gold was discovered at the Ovens in 1861. Within two months there were over 600 people panning for gold on the beach and mining the cliffs. The caves eroded naturally but Tucker's Tunnel was extended by mining.

Now the Ovens is a beautiful park and campground.

To learn more about Lunenburg County / The Ovens please go here.

Malagash

The first salt mine in Canada was in Malagash, Nova Scotia. It operated from 1918-1959. Can you guess where the mine was located in the satellite image? Probably not. Reclaimed mines blend back into the environment!

Marble Mountain

It looks like a tropical paradise but it's actually Cape Breton's Marble Mountain. Its white sand beach and turquoise water are the result of a marble quarry that operated there from 1869-1921. Crushed stone was pulled into the water by waves, making the beach white.

Because marble has high pH, it keeps the water at Marble Mountain soft and clear. This lets you see the white sand underneath better, making the water look turquoise. In fact, the marble's pH offsets damage from acid rain and helps keep the entire Bras D’Or Lake healthy!

Mica Hill

Mica Hill, named for its mica deposit, is in the Cape Breton Highlands National Park. Extraction took place there in the mid-1880s.

Milford

The eagle has landed!

At the largest surface gypsum quarry in the world in Milford, Hants County, the operator has dug several pond in a reclaimed area of the site. The ponds provide aquatic plants and animals new habitat and gives wildlife water sources. The company also built an island in one of the ponds to attract animals like ducks and geese, which visit the quarry in large numbers, partly because there are many cornfields in the area. The island gives the birds some protection from coyotes and foxes which are also native to the area around the quarry.

In the middle of the island, the company installed an upside-down tree to give raptors (eagles, hawks, ospreys) a place to nest. Raptors are regularly seen in the area. The tree is upside-down so its roots can serve the role of branches and give eagles room to nest.

The ponds and surrounding reclaimed areas are examples of the modern mining industry’s practice of "progressive reclamation" - reclaiming areas of a mine/quarry where extraction is complete while continuing to mine elsewhere on-site.

Moose River

Modern mines can sometimes fix issues with historical sites by cleaning up tailings. For example, gold mining first took place in Moose River in 1876. The modern Moose River Gold Mine is cleaning up historical tailings by digging them up and placing them in a special cell in the mine's tailings facility to contain them and ensure they don't continue interacting with the environment.

Newport Station

Former mines and quarries often become parks and protected areas! The Irishman’s Road Recreation Site in Newport Station is an example.

The Mosher Quarry, also later known as the Windsor Gypsum Company Quarry, operated from 1891 to 1934. Today, the site is part of a greenspace that includes soccer fields, forest and trails.

To learn more about the quarry please go here (https://notyourgrandfathersmining.ca/windsor-gypsum-company).

Nictaux Granite Quarry

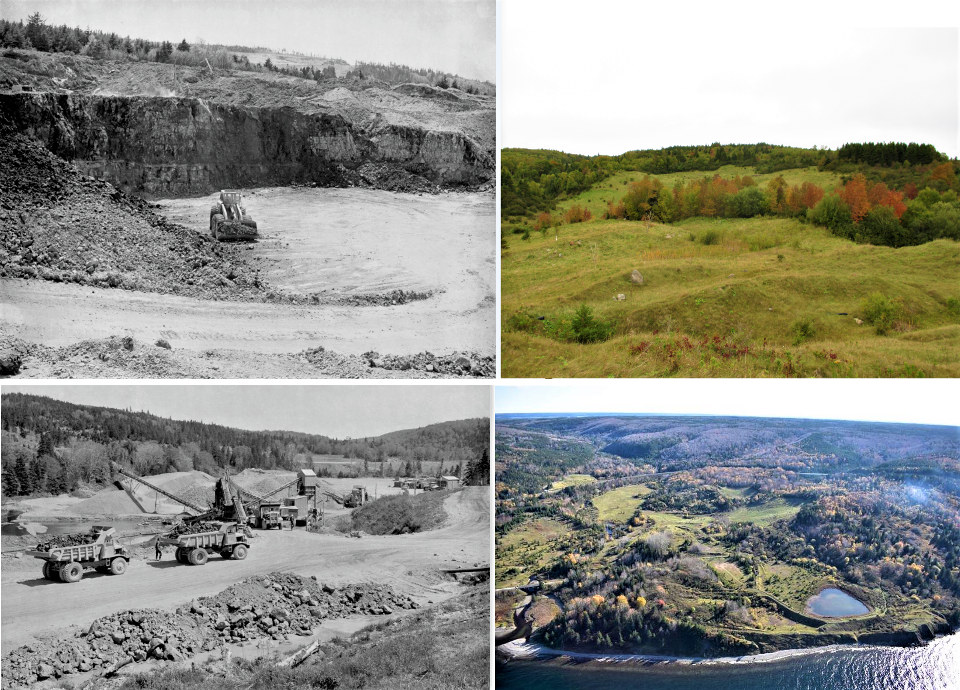

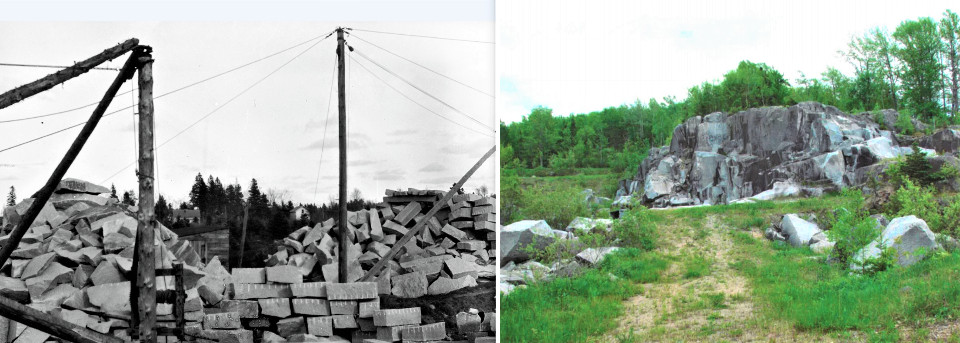

The Nictaux granite quarry, before and after!

Granite was quarried in Nictaux, Annapolis County, from about 1889-2007. Most production was for headstones, bases for headstones and other monuments, and blocks of stone for building foundations.

Point Aconi

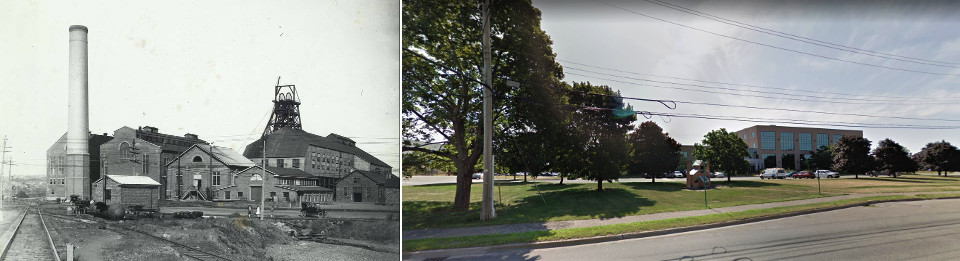

The Point Aconi coal mine, before and after!

A surface mine operated at Point Aconi from 2006-2013 and today the site is greenspace with ponds and ocean views.

It’s a great example of reclamation mining – cleaning up historical mines by completing extraction and returning them to nature or preparing them for other uses. The mine was on the site of the old Prince Mine, which opened in 1975 and closed in 2001.

The modern Point Aconi surface mine extracted the remaining near-surface coal and cleaned up the site from the Prince Mine’s activities – at no expense to taxpayers since the reclamation was funded by selling the coal to Nova Scotia Power.

The surface mine also cleaned up the remains of extensive historical bootleg mining operations: tunnels, tools, equipment and pillars of coal left in place to hold up the ground above. The site had many sinkholes caused by the bootleg mining - locals would extract coal to heat their homes in generations past. The reclamation mining fixed these subsidence issues and stabilized the site, making it safe for future use.

To learn more about Point Aconi please go here.

Shelburne, Islands Provincial Park

370 million-year-old "Scotia Grey" granite from the Shelburne Island Park Quarry helped build many Nova Scotia buildings including the Shelburne Post Office and the old Chronicle Herald building in downtown Halifax.

Today, the quarry is part of the Islands Provincial Park.

Spryfield

Spryfield’s Ravenscraig sports field is a former quarry!

The pictures below show the site in 2005 as development was about to begin and again in 2017 after the area had been turned into a residential neighbourhood with a soccer field, playground and hiking trails. The slope of the former quarry is used for sledding by local families.

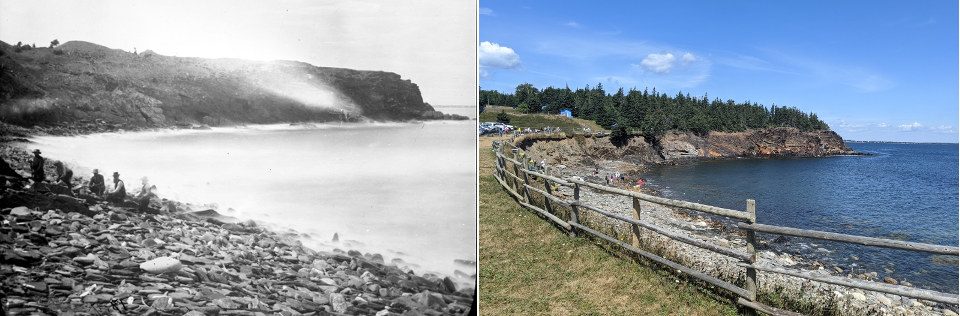

St. Margaret’s Bay

There are countless small, old quarries throughout Nova Scotia that helped build the province. This former quarry, now a swimming hole, in St. Margaret’s Bay is an example.

Quarries like this are often called “wayside” quarries in the industry, meaning they are small and used only temporarily or infrequently.

St. Rose

The Evans coal mine in St. Rose was first mined in 1946 and it was a reclamation mining project in the early 2000s. The last of the coal was extracted and the site was reclaimed by returning it to nature.

To learn more about St. Rose please go here.

Stellarton Coal Mine

200 years of pick-and-shovel mining, including bootleg mines, left this land in Stellarton unusable. The Stellarton coal mine reclamation project is stabilizing the site and making it possible to build on. Reclamation mining cleans up historical mine sites by completing extraction and returning them to nature.

To learn more about Stellarton Coal Mine please go here.

Stellarton, Allan Mine

Reclamation usually means returning a mine/quarry to nature but it can also mean preparing it for development. Today, the former Allan Mine (1904-1951) in Stellarton is the site of Sobeys’ headquarters.

To learn more about Stellarton, Allan Mine please go here.

Stellarton, Dorrington Softball Complex

Today it’s the Dorrington Softball Complex but it used to be the site of a coal mine!

The first of the Bye Pits was sunk in 1827. Now the site is home to the Stellarton and Area Minor Girls Softball Association, an organization that provides females ages 4-18 the opportunity to play fast pitch softball at the recreational and competitive levels.

To learn more about Stellarton, Dorrington Softball Complex please go here.

Stellarton, Foord Pit

The Museum of Industry doesn’t just have great info about things like Nova Scotia’s historical mines – it’s located on one of them!

The Museum is on the site of the Foord Pit which opened in 1866 and was the deepest coal mine in the world at one time – its shafts were 1000-feet deep.

To learn more about the Foord Pit, please go here.

Sullivan Creek

Sullivan Creek, on the Little Pond Road in Cape Breton, was mined from 1993 to 1998.

It's one of several mines reclaimed around Alder Point, Cape Breton, in the late 1900s and early 2000s - examples of how mining makes temporary use of land and then land can be used other ways.

To learn more about Sullivan Creek please go here.

Thorburn

Coal mining started in Thorburn in 1867 and ended when the site was reclaimed by a modern mine that ran from 1997-2000. The last of the coal was extracted, historical buildings and equipment were removed and the site was returned to nature.

To learn more about Thorburn please go here.

Truro, Kiwanis Park

Truro's Kiwanis Park is a former gravel pit that provided aggregate in the 1930s to build Route 2. It was reclaimed in the 1950s by the Truro Kiwanis Club.

Each spring, the Cobequid Salmon Association organizes a popular Fisherama at Kiwanis Park for kids, and the park now has so many ducks that the town asks residents not to feed them in order to help manage the population.

Walton Gypsum Quarry

When gypsum mining started in Nova Scotia in the 1700s it was done by farmers, not miners. Gypsum from farms was exported from Windsor to the United States for use as fertilizer. Today, the main use of Nova Scotia gypsum is wallboard/drywall production, although a little is still used as fertilizer.

The Walton Quarry in East Hants started producing in the 1800s and continued until 1972. Today the quarry, like many other former mines, is a lovely lake.

Walton Barite Mine

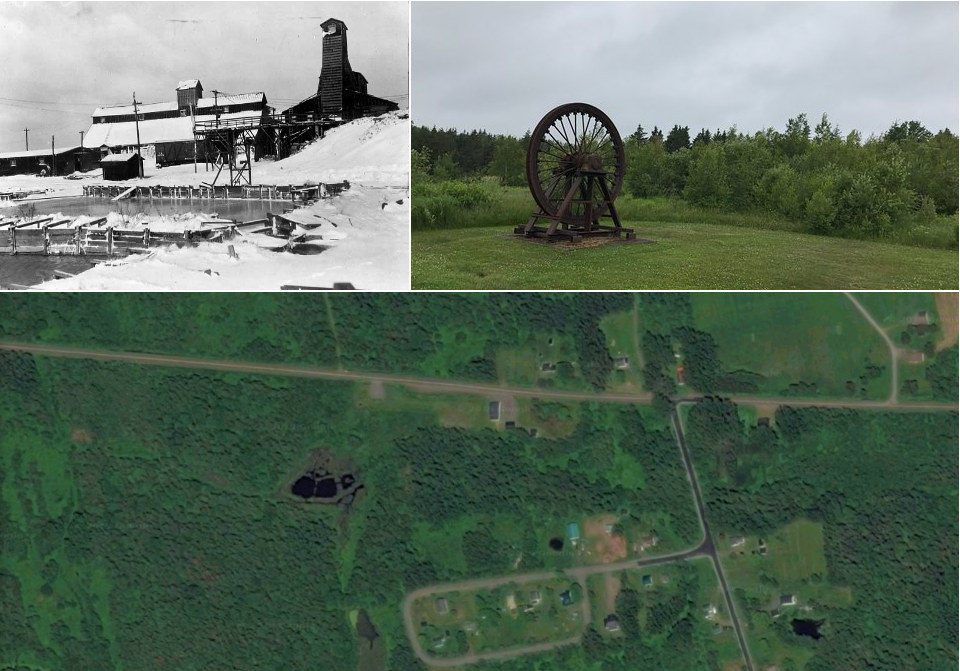

The Walton barite mine, before and after!

One of the biggest barite deposits in the world is in Hants County. It was mined from 1941-78.

Today it's a lovely lake and greenspace.

Westville, Acadia Park

Acadia Park in Westville is on the site of the former Drummond coal mine, which was mined underground from 1868-1984. A surface mine operated in the 1980s and 1990s to complete extraction of the coal and reclaim the site.

Today the former mine is acres of greenspace and parkland which includes a playground, pond, gazebo, baseball field and heritage signage. The reclamation also fixed subsidence issues so land left unusable by historical mining could be developed.

To learn more about Westville, Acadia Park please go here.

Amherst, Red Stone Quarry Blockhouse Cheticamp CoalburnCottam Settlement Dartmouth Crossing Dartmouth, Leighton Dillman Park Dartmouth, Shubie Park Dingwall Gold River Halifax, King QuarryHalifax, Merv Sullivan Park Halifax, Point Pleasant Park Halifax, Terence Bay Wilderness Area Inverness Irish CoveKempt Shore Lunenburg County, The Ovens Park Malagash Marble Mountain Mica Hill Milford Point Aconi Shelburne, Islands Provincial Park Spryfield St. Rose Stellarton Stellarton, Allan MineSullivan Creek Thorburn Truro, Kiwanis Park Walton Gypsum Quarry Walton Barite Mine Westville, Acadia Park